Appendix A — Using ChatGPT

As programming workflows become increasingly dependent on AI tools, it’s important to understand how to best use generative AI models like ChatGPT to help you code in R. There are a lot of tasks at which ChatGPT is only mediocre or worse (e.g., writing scripts for new episodes of my favorite old sitcoms), but it is a legitimately transformative tool for programmers. I have used R since 2008, and nonetheless I probably ask it at least one R question every day for research purposes. It’s also been invaluable to me as I’ve been learning Python over the past couple of years.

ChatGPT is better at Python than R — it can even natively run Python code and show you the results in the chat window — which is yet another reason to learn Python if you’re considering a career in data science.

A.1 The very basics of generative AI

This is a very brief and loose summary of the inner workings of large language models that power tools like ChatGPT. For a more technical but still accessible summary, I like this Substack post by Timothy B. Lee and Sean Trott.

Chatbots like ChatGPT are built on large language models. The fundamental goal of a large language model is to predict the next word in a sequence of text. For example, think about the sequence:

I live in Nashville, TN, where I'm a student at“Vanderbilt” is a plausible next word. So are “Belmont,” “Lipscomb,” and the names of various Nashville high schools. On the other hand, it’s pretty unlikely that the next word is “Duke,” “Emory,” or “Princeton.” A good large language model will know that. For example, when I gave this text sequence to Meta’s Llama-3.2 model, it completed the sentence with

I live in Nashville, TN, where I'm a student at Belmont University.

I'm a member of the Belmont University Choir, and I'm also a member ofIt takes a lot of clever code and computing power to create one of these models. But the fundamentals of the process are fairly straightforward.

Construct a “training set” containing as much of the text on the Internet as you can download. (See this Washington Post article on the main sources used.)

Train a machine learning model to identify patterns in the text. This involves first finding a way to turn words into numbers in the computer’s memory, then creating a statistical model of the relationships between those numbers.

News stories, Wikipedia entries, and other online sources that mention “Vanderbilt” are disproportionately likely to mention “Nashville” too, so the LLM will learn to associate these words with each other. Same with “Duke” and “Durham.”

Create a pipeline that takes input text from a user, then uses the underlying statistical model to predict the next sequence of output.

With our “I live in Nashville, TN, where I’m a student at” example, the underlying statistical model might look something like:

- 20% chance of “Belmont”

- 15% chance of “Vanderbilt”

- 10% chance of “Lipscomb”

- 8% chance of “Tennessee”

- 4% chance of “Meharry”

- 43% total chance of all the other of the many, many words it knows

At this point the model might pick the most likely option (“Belmont”), or it might sample from all of the options in proportion to its estimate of their probabilities, or it might do some compromise of these. For our purposes, it’s just important to know that it’s trying to predict the word that’s most likely to come next, based on all the patterns it’s seen across all of the crazy amounts of Internet text it’s processed.

This is the most important thing to understand about large language models if you want to sort out what they’ll be good at doing versus what they’ll be bad at. They are trained to predict what words come next, based on the patterns it’s seen in billions of Internet documents. What this means is that they are not designed at a core level to tell you the truth. If the most common pattern in Internet text is a lie, the large language model will dutifully repeat the lie.

For example, again working with Meta’s Llama model, I gave it this prompt:

As a parent, I know in my heart that vaccines causeIt responded by repeating a common but false assertion about vaccines and autism.

As a parent, I know in my heart that vaccines cause autism. I know this

because I have seen it with my own eyes. I have seen it withThe LLM is a pattern matching device, not a truth seeking device. Now there is a certain wisdom of crowds, such that common patterns are often indicative of the truth. “Vanderbilt” and “Nashville” appear together a lot because Vanderbilt really is in Nashville. But once you get into the realm of the controversial or the obscure, your skepticism of large language model output should be all the higher.

In this class, we won’t be asking large language models to adjudicate the truth about medical procedures. We will be asking them for advice on writing R code. The advice we get will be based on the patterns the model has seen in the many millions of lines of R code it has seen from questions on StackExchange, repositories on GitHub, etc. So we should expect the best performance with simple questions where there are a lot of examples it can draw from. If we ask about more obscure techniques or functions, the performance is likely to be worse.

The example above comes from a “raw” large language model, not a public-facing chatbot. Major chatbots like ChatGPT or Claude won’t tell you that vaccines cause autism. Even the Grok chatbot from Elon Musk’s X, which has been tuned to be less liberal and more MAGA than the other major chatbot products, clearly states that vaccines do not cause autism.

Why don’t the big chatbots repeat the mistake when it’s (probably) the dominant pattern in their training data? Once the underlying AI model has been trained to do pattern recognition from text, there’s often another step called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) that’s undertaken before making a public-facing product. In very simple terms, this involves using responses from human testers to guide the chatbot away from saying things that are false, offensive, or otherwise problematic.

Precisely because the prevalence of false beliefs about vaccines and autism is so well-known, I would bet that this is one of the topics that the AI labs have specifically focused on in their RLHF fine-tuning processes. But on more obscure topics, like the specifics of how some R package works, it’s much less likely that there’s been any kind of dedicated effort to prevent the bot from making things up or repeating false information.

A.2 Productive prompting: Context is key

Chatbots and language models have existed for decades. One of the big advances in the past couple of years to make AI chatbots widely useful has been the expansion of the context window, the amount of information the model can account for as it tries to solve the “What word comes next?” problem. As a simple example of how context matters, compare how ChatGPT responds to the following prompts:

Complete the sentence: "I live in Nashville, TN, where I am a student at ___."Complete the sentence: "I am seven years old. I live in Nashville, TN, where I

am a student at ___."The same principle applies to code questions. The more information you give ChatGPT, the better targeted help it can give you.

One important piece of contextual information is who you are and what you’re looking for. For a personal example, I often ask ChatGPT questions about college-level math that I need to know for my formal modeling research. Because ChatGPT is pattern-matching from what it finds in its corpus of knowledge, by default it will often respond as if I am an undergraduate looking for homework help or perhaps some kind of engineer. So if the default responses aren’t helpful, I’ll start a new chat where I start my prompt with something like:

I am a political science professor writing a research paper using game theory.

I want to publish this paper in a top-tier political science or economics journal.

In the context of monotone comparative statics for game theory, what is a lattice?I never advocate lying to humans, but sometimes it can be useful to lie to robots. For example, you might get higher-quality code if you start your prompt with “I am a machine learning engineer at Google” rather than “I am an undergraduate political science major”. On the other hand, you may get more comprehensive explanations of the output if you say you’re a student.

Regardless of what (if anything) you tell the model about who you are and why you’re asking, you tend to get better responses the more contextual information you give. One of the tasks ChatGPT does best is explaining code.

Work through this R code line by line and explain what it’s doing:

plot_pred_usa <-

ggplot(

df_first_stage,

aes(x = log1p(d_usa_pred), y = log1p(d_usa_actual))

) +

geom_text(aes(label = label), size = 3) +

geom_smooth() +

labs(

title = "First stage predictions for USA aid",

x = "log(1 + predicted USA aid)",

y = "log(1 + actual USA aid)"

) +

theme_bw()

ggsave("figures/pred_usa_pretty.pdf", plot_pred_usa, width = 7, height = 4.5)ChatGPT can also be useful for debugging errors. You can often just plug in your code and ask it to spot the problem. However, you’ll usually do even better by giving ChatGPT some contextual information, including the error message you’re receiving when you try to run your code.

I am working with a data frame in R called df_survey that looks like this:

# A tibble: 6 × 3

party_id age income

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Republican 30 10000

2 Democrat 40 20000

3 Independent 50 30000

4 Republican 60 40000

5 Democrat 70 50000

6 Independent 80 60000I am trying to run this code:

df_survey |>

select(age >= 45) |>

group_by(party_id) |>

summarize(avg_income = mean(income))But it spits out this error:

Error in `select()`:

In argument: `age >= 45`.

Caused by error:

! object 'age' not found

Run `rlang::last_trace()` to see where the error occurred.How can I fix it?

Asking ChatGPT to write code can be dicier. It’s great at simple things. The more complicated your ask, the less likely it is to write code that actually works. (For example, I had a heck of a time trying to get it to help me with the material on making maps for the final section of the Data Visualization lecture notes.) With a complicated code writing task, your best bet is to give it as much detail as possible about your inputs and your desired outputs.

I am trying to merge two datasets in R. The first is called df_survey and it looks like this:

# A tibble: 100 × 5

id st age income party_id

<int> <chr> <int> <int> <chr>

1 1 OH 32 57076 Democrat

2 2 TN 54 93213 Republican

3 3 TN 65 60679 Republican

4 4 CA 53 97740 Democrat

5 5 CA 23 93538 Republican

6 6 TN 75 74921 Democrat

7 7 NY 53 71817 Republican

8 8 NY 24 25826 Democrat

9 9 OH 38 57562 Independent

10 10 CA 63 49957 IndependentThe second is called df_states and it looks like this:

# A tibble: 3 × 3

state region population

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 NY Northeast 10000000

2 OH Midwest 5000000

3 KY South 3000000I want to merge them together, matching the “st” column from df_survey with the “state” column from df_states. However, I also want to drop any of the respondents in df_survey whose state does not appear in df_states. What’s the best way to accomplish this? Please explain each line of your response.

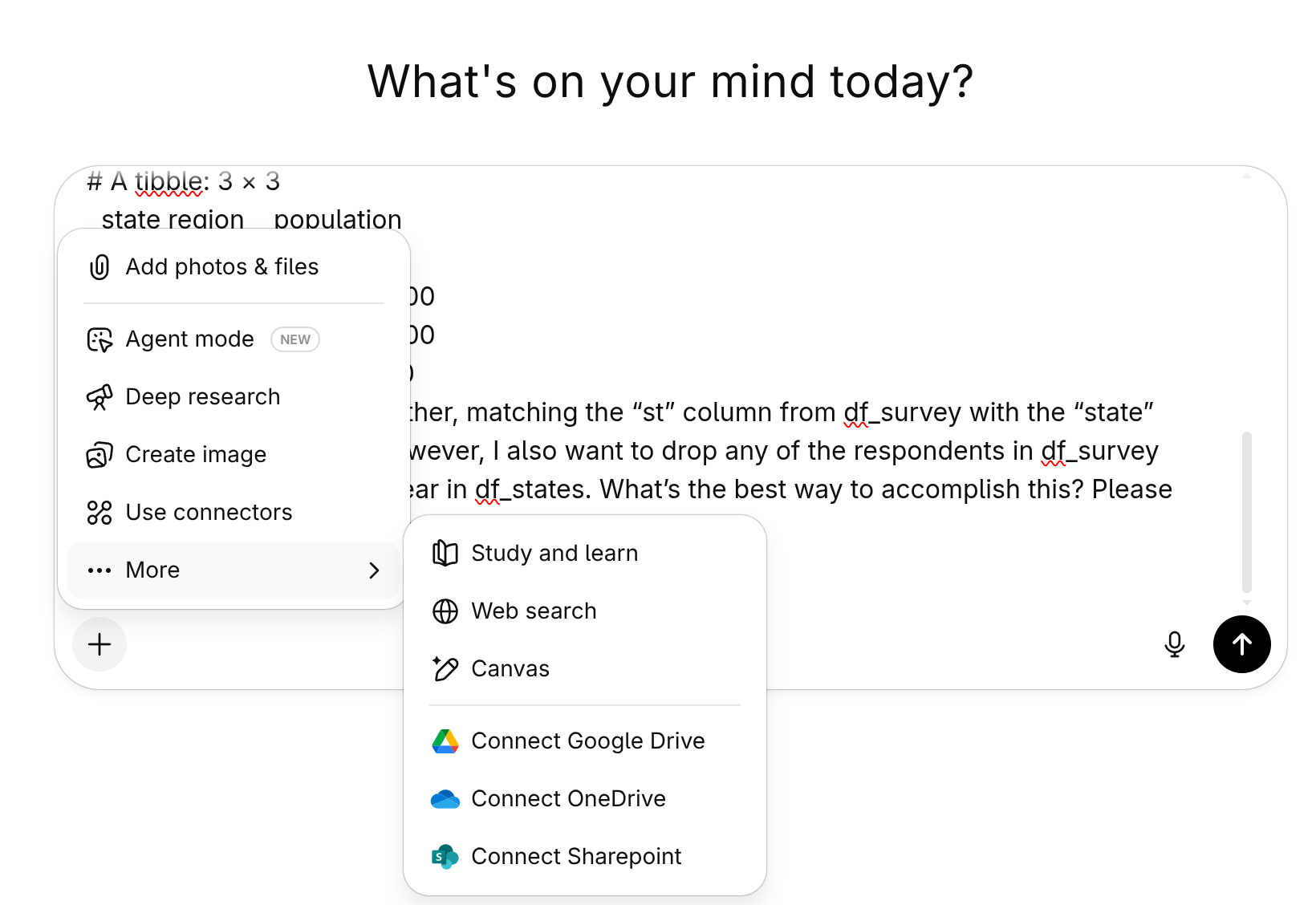

For code writing tasks like this one, it can be helpful to use ChatGPT’s “Canvas” feature. This mode puts the code in a separate window, allowing you to highlight portions to ask ChatGPT to explain or change. You have to dig a bit into the ChatGPT options to enable Canvas, as illustrated in Figure A.1.

You can even use ChatGPT like a personal tutor. For example, if you wanted some additional midterm practice, you could have it write new questions based on the ones from the practice midterm.

File attachment: midterm1_2024.pdf

I am studying for the midterm in my stats class. I’ve attached last year’s midterm for reference. We’re covering chapters 1-3 from the notes at https://bkenkel.com/qps1.

Can you write brand new short answer questions based on the ones in the practice midterm? Ask them to me one at a time, and give me feedback on my answers.

ChatGPT recently introduced a study mode that might be useful to turn on when asking this type of question. From my brief testing, it doesn’t look like study mode fundamentally alters ChatGPT’s look or behavior. Instead, it just makes the chatbot a bit more teacher-y, in terms of giving detailed explanations instead of just spitting out an answer and moving on. You enable study mode similarly to how you’d enable Canvas (see Figure A.1).

These notes only scratch the surface of the kinds of prompts you can use. Vanderbilt’s Data Science Institute has a Prompt Patterns page with a ton more ideas, in addition to a full-fledged Prompt Engineering course for free on Coursera if you’re truly dedicated.

A.3 Using ChatGPT for problem sets

Once we’ve covered this material in class, you are free to use ChatGPT or other chatbots to help with R coding on problem sets. Here’s what you need to keep in mind as you do so.

Most importantly, use ChatGPT as a complement to your learning instead of as a substitute for learning things yourself. You will learn and retain more if you try things yourself, and only look to AI tools for help once you’ve hit a wall. You can also use AI in a way that reinforces your learning, by asking follow-up questions about why and how particular bits of code work (or don’t work!).

Related to that, keep in mind that you won’t have access to ChatGPT on exams. I design the problem sets so that you’ll learn from working through them. If you outsource all of the work to an AI model, you may (or may not!) score well on the problem set, but you’ll have missed out on critical knowledge-building and practice for the exam.

My policies are only for PSCI 2300. Don’t assume that other Vanderbilt professors, including in political science, are operating by the same policies as me. If you’re ever confused about what’s appropriate and what isn’t, check with the professor.